Precarious work in Ireland Part 2

Just days before Christmas 2017, the European Commission issued a proposal to member states to make working conditions across the EU more predictable and transparent. In it, they highlighted that across Europe, there are between 4 and 6 million workers working “on-demand” or on intermittent contracts. Another 1 million are subject to exclusivity clauses where they cannot work for anyone else; even if their current employer is not offering them sufficient work! And of those in temporary work, only a quarter transition to a permanent role.

But these figures do not present a full picture of precarious working conditions across the EU and in Ireland, we do not have a good grasp of the scale of that type of work in this country.

By its very nature, the concept of precariousness is hard to define.

Those tasked with looking at these labour market issues; the International Labour Organisation (ILO), Eurostat, Eurofound and the European Commission employ a range of definitions for insecure and precarious work, but we can combine them to characterise precarious workers as those that find themselves uncertain with regard to working hours required and their tenure or security of employment, vulnerable with regards to the amount and frequency of pay and unsupported with little or no access to state supports in terms of jobseekers benefit because of the hours and days they work.

However, the numbers only tell part of the story. This is where some commentators fall into the trap that if it isn’t measured, they don’t believe it. The reality is that there is no full comprehensive measurement for what we believe to be precarious work. And the reason for that relates to the issue of risk.

Risk is the defining characteristic of insecure work and the greater the risk or responsibility borne by the worker as opposed to the employer for a worker’s security of income, stability of employment and access to social security, the greater the precariousness of that job.

Not all insecure work such as self employment is necessarily precarious. Although we know that in 2016, some 41% of Class S PRSI contributors (self employed not including proprietary directors) had a gross income of €20,000 or less. Similarly we know from the dependence on the family working payment (formerly FIS) that not all full time permanent work guarantees adequacy of income. Looking from the outside in, a worker with a permanent contract may appear secure but their variable hours and inconsistent income tell a very different story.

In that context, no single type of work or occupation can be classified as precarious.

However, we understand that those in full time temporary employment and those reporting as being in part time under-employment are at most risk. CSO labour force survey data suggests that in 2017 just over 175,000 workers found themselves in this situation. Alongside this, the Department of Social Protection has produced a very conservative estimate of 7,500 workers in disguised self employment, a figure many at the coalface of recruiting union members in the construction sector would contest as too low.

The focus on precarious work to date has been on worker’s lives and rightly so. The recent report by Tasc “Living with Uncertainty” excellently details the day to day lived experience of those working in precarious jobs and the adverse implications arising from this work life for housing security, self care in terms of health and family formation decisions.

Similarly, there has been a lot of research undertaken internationally on the lifetime impact of initial world conditions when young workers enter the labour market. Well known work by Autor and Houseman (2010) in the US looked at the so-called stepping stone effect from temporary agency work and fixed term contract work into permanent work and the initial work experience on employment prospects and lifetime earnings. Compared with fixed term contracts, those in temporary agency work had a lower probability of getting permanent employment and endured a larger earnings penalty over a longer period.

CSO’s labour force survey data tells us that the share of young workers aged 25-34 in temporary work has been edging upwards over the past two decades. In 1998, some 6% of all 25-34 year olds were in temporary work. At the height of the economic crisis here, this share rose to 10% in 2012 and it was 8% in 2017.

With regard to part time, almost one quarter of all those in employment in 2017 under the age of 35 were in part time work, up from less than a fifth (18%) back in 2008. If we consider that a share of younger workers are combining work and study, this figure alone need not give cause for alarm, provided young workers have access to consistent hours and decent pay, irrespective of the contract type.

However, 10% of those aged 24 and under who are working part-time reported being under-employed. It is these workers that we regard as being in a particularly precarious work situation. While we don’t know the precise reasons for that underemployment, there are strong grounds to believe that this is part of the exploitative culture in certain sectors where “if and when” contracts and variable hours exist.

Precarious work is not new. What is new is that precarious work is now emerging in sectors previously thought unimaginable such as third level education and that for some sectors, particularly those that rely on digital platforms, their business model or the very basis of their business depends on precarious work practices to operate and survive. We know from the CSO’s labour force survey data that in the education sector, just one in eight workers were on temporary contracts in 1998. It was one in seven in 2017.

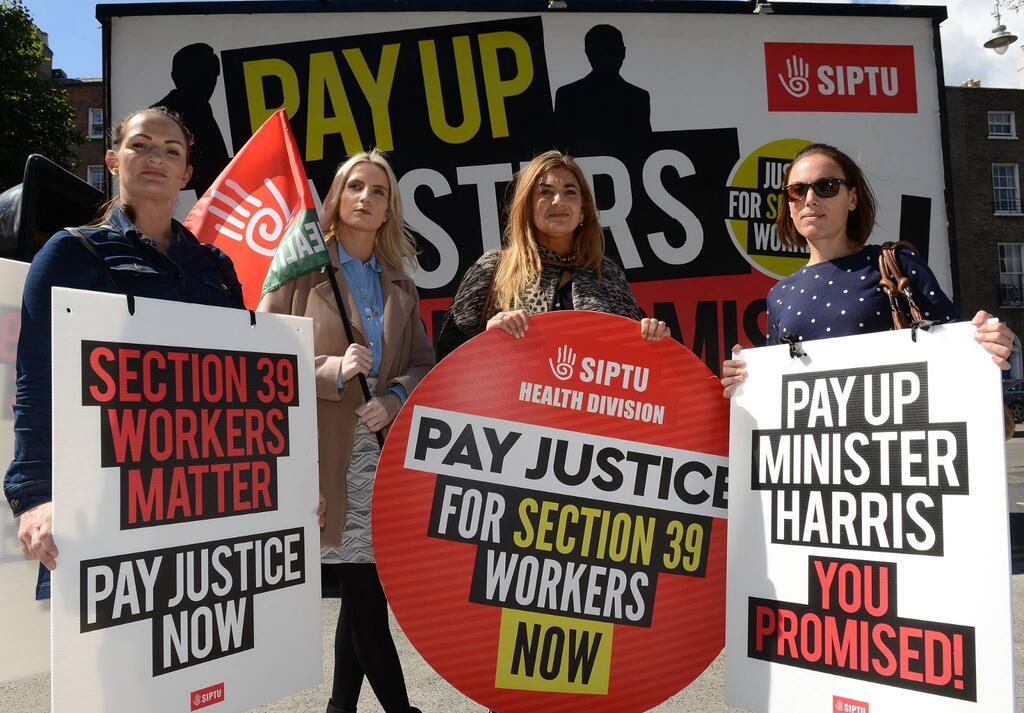

How workers respond to this challenge will be crucial. Many SIPTU members have found themselves on permanent contracts but working variable hours in sectors such as logistics, distribution and aviation. It was only when workers came together as SIPTU members and made their case collectively that they were able to achieve higher levels of guaranteed paid hours.

In the health sector, thousands of home helps achieved a major breakthrough earlier this year when together as SIPTU members they fought and won the right to increased hours and better conditions. And in the third level education sector, SIPTU’s work has ensured full time lecturer status for many who were previously in ill-defined lecturing roles with uncertain hours. Our goal is to ensure that university lecturers can access secure, decently paid employment contracts and we are now at the stage where Government now accepts this principal via the recommendations of their commissioned report produced by senior counsel Michael Cush. Our next step is to ensure it is implemented.

For SIPTU, the motto is simple; united we bargain, divided we beg.